Writer Scott Rodd sat down with Bishop Nehru in the home he grew up in to speak on his new album with the ever enigmatic Doom, the Perils of the rap game, porn & more.

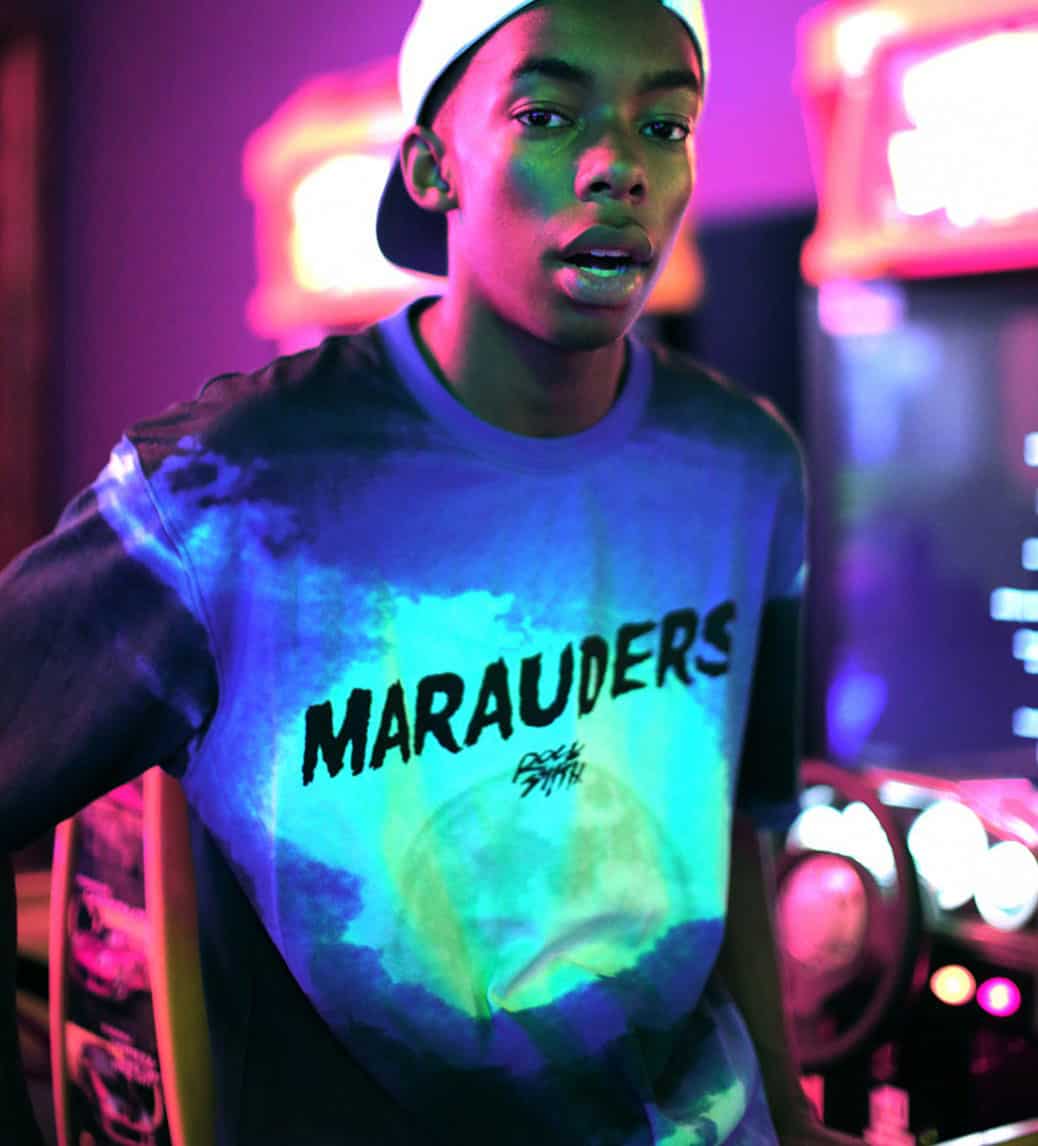

When I arrived at Bishop’s house—a small, austere ranch painted a pale yellow—a man wearing a wife beater waved me through the gate leading to the backyard. He introduced himself as Jen, Bishop’s father. He took a drag of his Newport menthol and told me I could have a seat at the table in the yard. He was soft-spoken and seemed like a man of few words, but that isn’t to say he was unwelcoming. I sat at the table and surveyed my surroundings. A basketball hoop stood at the back of the yard before a patch of dirt, and in the corner against the fence was some workout equipment. Children played loudly in the next yard over, and a car alarm went off in the street. The neighborhood had the feeling of a suburb that couldn’t quite escape the long reach of NYC’s urgency and urbanity. Suddenly a subterranean bass sounded from the basement of the house, and a few minutes later Bishop emerged. Tall and wiry with a hat slapped on backward, he didn’t walk like an awkward teen still growing into his body, but rather a prodigy carrying the future of hip hop on his shoulders. He stuck out his hand as he approached and said in the same soft-spoken voice as his father, “I’m Bishop, nice to meet you.”

The Source: I’m gonna start with a quote from the song “Introvertz” off your mixtape strictlyFLOWZ: “I’m used to being alone just me and symphonies/ Now I’m never prone and these interviewers are sent to me.” So, before we begin, I want to thank you for taking the time to speak with me—and maybe offer something of an apology.

[Laughs] Nah no problem. No problem.

Did you grow up in Nanuet?

Yeah.

I had about 20 minutes to kill before I came over here, so I put on Nehruvia and drove around town. It added almost a new dimension to your work—listening to your music and seeing the place you grew up. Does your music have a strong connection to place?

I guess it may, in a way. Of course, your location and the things around you always influence your character. So you could say I was influenced by the things around me, but I always tried not to gravitate towards that too much, tried to have my own view on everything.

Right, not have those things overwhelm you.

Exactly.

As a rapper you embrace being from the suburbs, and I’m curious—what does it mean, to you, to be a rapper from the suburbs?

I guess the same thing it means to be a rapper from an urban scene or a city. It’s just—we’re the same people, you know? I don’t think location has anything to do with it. I don’t know why you can’t be—well, people don’t really say you can’t be a rapper from the suburbs, but…

There’s almost a kind of stigma against it where people don’t expect you to be—

A rapper from the suburbs.

Or at least a legitimate rapper.

Exactly. But usually suburban artists are more into the musical thing—being in marching band and understanding music theory, and those are the things I always paid attention to in music class. So I think it’s kind of disrespectful to say that I can’t be from the suburbs and be a rapper, because I can do more than rap. I can play piano, I can put chords together, I understand intervals, I know the difference between a half step and a whole step—and a lot of artists don’t. A lot of people don’t that are rappers. So I feel kind of disrespected when people say I can’t be from the suburbs and be a rap artist.

To quote from your song “77”, “I was the type of nigga who write about lightin’ triggas/ but then I realized those lines were real lies.” Is there a compulsion in hip hop to rap about urban life, street violence, drugs, etc., that you have to fight?

Well, for me, that’s about being of naïve. I was probably 12 or 13 writing about stuff like that. So it was probably the stuff that was mainstream and me just wanting to make music to be famous instead of making music with a purpose for myself. And as I got older, I started to realize like, nah, I don’t really have that passion to make music to be famous—I actually enjoy it as a hobby. And once I had that love for music, it became something I could use to vent, something I could use to help others get through hard times, and, you know, share my emotions and views on certain things. And there’s kind of no block on it as well—I can say it as censored as I want or as uncensored as I want. So that’s what’s dope as well, and kind of why I got more into music.

You’ve spoken about your appreciation of rap’s Golden Age, and your music—both the production and lyrical content—reflects this.

Alright, I wanna stop that. [Laughs]

Yeah definitely correct me if I’m wrong.

The Golden Age—I am influenced by it, but I’m more influenced by, let me see…more neo-soul artists, jazz, R&B, synth-pop. Honestly, I don’t even really listen to rap, but the rap that I do listen to is Golden Age rap. I do listen to some crazy trap shit—I listen to Chief Keef and people like that, I fucks with them. I’m a guy that listens to all types and genres of music just because of my appreciation for music as a whole. I understand like—I can hear a melody, and the lyrical content may not be dope, but the melody in which the lyrical content is being said may be dope. That’s why there are so many musical genres that I appreciate. But the Golden Age was more rap music that I listened to—I was not as a whole influenced by it.

Cause if you listen to a lot of my early stuff, the first projects I made weren’t even rap projects. The first project I made was a jazz project, and after that it was a sample project, Mellow Beach Samples. And after that, I made a project that I produced myself called Kanvas, which sounds nothing like the Golden Age. It’s actually influenced more by Pharrell and synth pop and Dam-Funk. A lot of synth instruments and pads in it, a lot of harpsies. It’s just things that bring out certain types of emotions, and it’s actually more explicit than my stuff now [laughs]. Because you can’t have an angry sounding track and not be angry on the track. It would make a song, but it wouldn’t make a powerful song, a timeless song. So when I hear certain things, if I hear that emotion, I 100% go with that emotion, because I know that’s just the emotion I know other people are gonna get when they hear it, you know? Because that’s how I got it.

You’ve stated that artistic control over the things you produce—music, videos, etc.—is very important to you. Why, specifically, do you prize artistic control?

From the beginning, that’s why I started making music. To have my art be my art. That’s why I think any musician would want to make music. Not even as just a musician but as, like, a photographer. You don’t want to take a picture and have someone else come edit the picture. You’re gonna want to do it yourself, edit it yourself.

Makes me think of Woody Allen and the idea of the auteur. He has complete control over his movies, but one trade-off has been that studios don’t give him a whole lot of money to make his movies, so a lot of actors have to star in his movies pro bono or for very little money. Do you think there’s something you might be sacrificing for having complete artistic control over your projects? Do you see that there might be similar limitations for you?

I mean for sure, I’ve seen them already a bunch of times. It sucks, it really does suck. Because like, it’s not even that people don’t want your artistic vision—it’s just that they want to help with the artistic vision. And sometimes you just see something so straight you don’t want anyone to interfere with it, even if it may be them thinking they’re helping. Like sometimes someone will come in and I’ll be like, ‘Yeah that’s a dope idea, let’s do it,’ and we’ll go and we’ll work off of it and both collaborate with it. But usually, lately, I’ve been writing my own treatments, been writing screenplays cause I want to get into directing. And it’s been hard to get the things that I’ve been seeing budgeted correct, because sometimes they’re like, ‘Well I don’t know if this video will be, you know, worth the budget,’ you know what I mean? And the budget might be—a pretty big number I can’t lie [laughs], because some of the ideas I have are amazing ideas. But sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.

But it sounds like that’s a sacrifice you’re willing to make if it means having artistic control.

Money—?

Yeah

Yeah any day, any day. I’ll sacrifice—I don’t put money over everything. I feel like it’s the other way around completely. It’s my artistic vision over the money 100%. But that’s the problem, that’s what it is. Other people don’t see it like that—other people are hungry for the money. So when you do find that company or group of people that are like, ‘Yeah we’re with the artistic vision 100%,’ it’s like all right dope, and then you get to have that awesome collaboration.

You’ve talked about the troubles you’ve had at school—an inability to stay engaged in classes, challenging administrators, even being put on educational ‘probation.’ Is finishing up school a priority for you?

I really want to, because I want to go to film school—I want to go to college really, really badly. Really, really, really badly—I think it’d be fun. I think it’d be an experience in a whole, especially for networking purposes. That’s something that I’ll probably need in the future—definitely need in the future. So yeah I definitely want to do that.

In a way, your situation reminds me of Nas’ story—dropping out of Cooley High and then schooling himself through reading the Bible, Quran, and other seminal texts. Would you similarly describe yourself as an autodidact? That is, someone who seeks the things he wants to learn on his own and teaches himself?

Yeah—yeah I think you have to be like that. I think everyone should be like that. Everyone shouldn’t just take what’s presented to them. You have to search for yourself, look for yourself. Get your own view on things.

Do you enjoy reading?

Yeah I have a bunch of books in my room. I knew you were gonna ask me that, too. I was in the bathroom lookin’ in the mirror, putting on my hat thinkin’, ‘I feel like he’s gonna ask me about books.’ [Laughs]

Do you have any favorite authors?

I mean, I don’t really have any favorite authors, but I read all kinds of different authors. Right now I’ve been reading Joshua Stone, he writes about ascension—he has a whole fucking series of books. I’ve been into those—it’s more European teaching of theology. But I’m just dabbling with it, just to see what it’s about to see how other people view certain things.

So back to music. You’ve aligned yourself with two hip hop stars, Kendrick Lamar and DOOM, who, while each highly skilled in his own right, represent two totally different camps of hip hop. Kendrick has immersed himself in the limelight, garnering awards and accolades and fixing himself at the center of pop-culture. DOOM, on the other hand, never shows his face in public, eschews social media, and even sends imposters on stage at his shows. He’s a hermit in every sense, and it only makes his fans want him more. What will you take from either one of those rappers as you progress? Do you see yourself leaning towards one camp or the other?

To be honest, I don’t really know. I feel like the way people view me now is the DOOM way, like, ‘Who is he? Where is his face?’ I kinda like that, but at the same time I do want awards—I do want Grammys, I do want video awards, I wanna sell out MSG. I wanna sell out MSG super badly. You know how Justin Beiber sold it out in like, what was it, seven minutes?

Yeah—you wanna beat that?

[Laughs] Nah I don’t wanna beat it, I just wanna be able to sell out MSG period. I think that would be amazing—and like now, at this age. Maybe not 17, but 18 or 19. While I’m still young, I wanna do that soon.

You’ve talked about how DOOM’s had a very positive impact on your technical skills as a producer. But in addition to being a venerable producer, he’s also an artist who was severely scared by the music industry. He went from a rising start in the rap game to getting spit out and hitting bottom. It was one thing after another—the rejection of KMD’s sophomore album Black Bastards, being dropped from his label, his brother Subroc dying, and eventually becoming damn near homeless. When he came back, he did so with a vengeance—intent on exacting revenge on the rap game and the music industry from behind the mask. So, in addition to the technical guidance he’s given you working behind the boards, has he given you any paternalistic advice about the rap game based on his experience? Ways to survive and thrive in the music industry?

In a way, somewhat. With production, he taught me about sampling—I was already keen with making beats of my own straight off rip, but I sucked at sampling. That was something I needed help with. But as far as information about the rap game and things like that, he told me a couple things. Like always keep my mind, don’t let anybody taint my mind. He said I know what I want. He was like, ‘You see it already, and I see that you see it—so just keep goin’ on your straight path and keep goin’ for what you see, and it’ll happen.’ And that’s kind of how NehruvianDOOM turned into NehruvianDOOM.

Cause he saw something in you and he saw that you knew what you wanted.

Yeah, like before it wasn’t even supposed to be a collab album. It was supposed to just be me and DOOM was supposed to produce. And then after a couple tracks came out, he was like, ‘I really see what you’re trying to do with this. I wanna get involved fully.’ So he got involved and out came NehruvianDOOM.

Must’ve been pretty exciting.

It’s fuckin’ crazy. [Laughs]

In a previous interview, you said you were in the back of the classroom in 9th grade and wrote down a list of goals, and one of the goals was to make an album with DOOM.

Yeah, you wanna know why I did that? All right, so Tyler the Creator tweeted one day to write in the back of your notebook all your goals and check those shits off. So I was thinking that’s actually a good idea. And later, as I started getting more into metaphysics and things like that, I learned when you write something down it kind of affirms it into the universe. Before that though, I was in the class and I wrote them down because I thought it was a good idea, and I wrote like ten shits down. And crazy enough, like all of them are starting to happen—it’s just crazy.

But the DOOM shit is even crazier than that. I used to argue with kids on the bus all the time that would say like ‘this dude’s the best rapper’ or ‘this dude’s the best rapper.’ And some of them are like the top stars now, so I can’t really say anything. But I’d be like, ‘No nigga, DOOM is nice—DOOM’s better than them.’ People would be like, ‘Who is he? I’ve never even heard of this guy, how’re you gonna say he’s better,’ and I’d be like, ‘How you gonna say he’s trash when you’ve never heard his song.’ And then I’d play some shit and they’d be like mind-blown, but I used to go to bat with kids all the time about DOOM. So working with him is amazing, literally a dream come true.

Tell me about your creative process with DOOM. You flew to England a handful of times to work in person with him on NehruvianDOOM, but there were gaps of time where you wouldn’t see each other and had to work separately on the project. Was this hard for you? Did the creative process suffer at all as a result?

No not at all, ‘cause when we were together we just got so much done so quickly. It was the power of labradorite, it was completely synchronistic. When we met up the first time, we knew the vision, immediately. The craziest thing is, we both—when we met and we listened to it together, we both understood immediately, and after that everything came together really smooth as far as the concept and mixing. We both knew like, ‘Oh this is the kind of sound we wanna go for and this is the direction we wanna take it.’ It’s not really a vibe that I could describe through any other genre, that’s why it’s so hard to describe—it’s just what we felt at the time. So, I think it’s gonna be dope to see how everything unfolds.

When DOOM was recording Madvillain with Madlib, the two lived in a house together for weeks but apparently hardly talked. According to DOOM, the two communicated through the music they were making. Was this similar to your experience with NehruvianDOOM?

I guess it kinda was. When we linked up though, when we were doin’ mixes, that was the only time we really spoke about much. As far as production, when we were in the stu’ the first time we linked up, DOOM was just playin’ beats. And he laid down a sample one time and I heard the shit and was like, ‘Oh man, I want this one—the way you just looped that, we need to do that shit now.’ And he looped it, he pitched it up, and I already knew what I was gonna do to it. So it’s kinda like, in a way we didn’t really communicate, we kind of just telepathically worked. That’s how the best music comes out, telepathically.

It’s clear that one of the themes of NehruvianDOOM is Eastern religion, specifically Hinduism—the recurring motif of the ‘third eye,’ moving from darkness into the light, the song “Om” and its theme of meditation. Even on the album cover, DOOM’s chain reads ‘om’ in Sanskrit. Tell me about the importance of Eastern religion to you and how it factors into the album.

Well, I am influenced by Hinduism—as far as India, “Nehru,” as you know. As of the past couple years I’ve been heavily into meditation and such. I found out about it in 8th or 9th grade, and a couple people told me not to do ‘cause it had to do with Satan or the devil, and I always thought of it like, I felt good doing it so I’m gonna continue to do it. In 8th or 9th grade I wasn’t too fond of Christianity, and that’s my parents’ religion and most of my friends’ religion, so it felt like I wasn’t being accepted too much. So I kinda just went on my own and found myself, embraced myself. And through embracing myself I found things like meditation, unity and serenity within, and unity with one and everything around you. So, through that I started to go through different teachings of Hinduism and Kundalini yoga and melanin in the brain and things like that. And more and more I kept learning about different things, like Eastern mysticism and numerology and astrology and theosophy—as I said before, it was just the thirst for knowledge, unlocking different doors. Even going back to Egyptian knowledge—that’s where a lot of Five Percent teachings come into play, and I try to embrace African knowledge as well as European and Western civilization knowledge. I just embrace all types of knowledge—whatever makes you feel right I think you should pursue.

No doubt. So does that theme of Eastern thought recur throughout the album?

Shoot—I mean it does, but I’d rather have people just listen to it to be honest. I don’t wanna toot anything—I don’t want people to get too excited or hung up on one thing. But it’s an album about—it’s straight from me, it’s like my emotions. There are tracks on there of me and DOOM just makin’ tracks, just feelin’ the vibe. Well, there is another track on Eastern knowledge, so I guess it does reoccur [laughs], but pretty much we were just feelin’ the vibe on the whole tape. The tracks with just me on them are pretty much my emotions, it’s more Nehruvia—it’s called NehruvianDOOM for a reason. All the fans of Nehruvia, they’re gonna love it, I can say that. My Nehruvians, they’re gonna dig it.

I’ll scratch my next question, then, which was, ‘What are other themes people should listen for on NehruvianDOOM?’

Just my heart—just listen for my heart. I’m speaking from my soul. When you’re listening, just know you’re listening to my soul.

Should fans expect any shows in support of the album?

Hopefully—I don’t wanna gas anything, but I hope so. I mean DOOM said he’s open for anything—I have a bunch of video ideas, I have show ideas, I have album release ideas, I have merch ideas. ‘Cause I’m a DOOM fan myself, that’s what a lot of people don’t understand. It’s not like out of nowhere I worked with DOOM. I’m a fan of DOOM—I’m a huge fan of DOOM—so I know what DOOM fans wanna see, what merch DOOM fans would go after. So I’m gonna embrace those and bring them out of DOOM, a lot—as much as I can I’m gonna juice it [laughs]. And he doesn’t have a problem with it, he’s like, ‘Nah let’s do it.’ So, I’m gonna juice it.

Last question—so you’re about to turn 18, what’s the first thing you do when you legally become an adult?

Hm…

Aside from go out and buy some cigarettes and porn.

Shit. Well I’m not gonna buy cigarettes—not gonna touch that shit, so that’s out. Probably buy lots of porn DVDs and posters though [laughs]. Nah but seriously—I gotta get a Lisa Ann poster and get that shit on my wall. Who else…Lela Star, Asa Akira. You’re gonna see, I’m gonna use it for a video. I’m gonna do another video in my room and have to blur it all out. You’ll see—remember this conversation.

———————

Bishop Nehru was chosen as The Source Magazine’s Unsigned Hype selection in issue #261. This friday we will be holding an Unisgned Hype event as part of our Source360 weekend. Buy your tickets for the event HERE

Scott Rodd is a writer living in New York City, his work has appeard in Salon Magazine, The New York Observer & more.