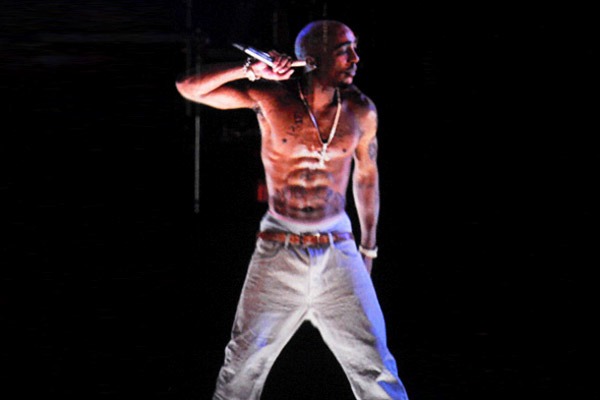

The 2Pac hologram that made its debut at the Coachella festival one year ago. It still begs the question: Is it okay to recreate an artists’ likeness for our own benefit?

In issue 253 we looked at one of the hottest stories of 2012… the Tupac Hologram. One year later we remember the infamous “What the f$#k is up Coachellaaaaaa!!!!” line.

—From Issue 253—

Those were the first words the world heard from deceased rapper Tupac Shakur at the 2012 Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival since his untimely death in 1996. The legendary MC left behind millions of fans that turned to pre-recorded songs and posthumous guest appearances to keep his legacy alive over the years. Though Rick Ross had declared ‘2Pac Back’ in 2011, Coachella really brought him back. Despite the fact that the hologram has been used numerous times before, it was Tupac Shakur’s HD virtual reflection that became the talk of the town. In 2001, Hollywood used holography to impose a then lifeless John Coltrane in the movie ‘Vanilla Sky’ portraying the jazz saxophonist as entertainment for a room full of preoccupied partygoers. The pop band Gorillaz sent their holograms to perform ‘live’ at the Grammy Awards in 2006. And Mariah Carey, Elvis Presley, Black Eye Peas, among others, have all had holograms created in their absence. In Japan, where anime graphics are light years ahead of the U.S., there is even a fictional hologram performer Hatsume Miku, whose party music and penciled-in looks sell out venues housing 20,000 people.

In the case of Hologram 2Pac (who even surfaced on Twitter a day later), a trick called “Peppers Ghost” (the reflection of an image that is projected on a Mylar screen which has also been used in countless movies) was used. The price of these projections are currently anywhere from $100,000 to $400,000, but with the rapid change and advance in technology, consumers could soon have 3D projections in their own living rooms for a much lower price tag.

“I think they honored him. I thought it was amazing and showed where technology is going,” says fashion specialist and longtime Tupac fan, Kiahnni Frierson. “Some people say let the dead rest, but at the end of the day most of these young artists look up to him. Internationally. I thought whether it was real or not, it felt good to see him onstage, because I miss him.”

Eclectic artists such as jazz musician Miles Davis, Prince, Andre 3000 and even DOOM often implicate their own rules when creating and deciding when and how they will share their music. Most musicians mature over the course of their career span. Is it fair to screenshot someone from the era you see fit? Or, do we give the fans what they want even when the musician is passed on?

“I had mixed emotions when I was watching it,” says West Coast-based MC Crooked I. “It was kind of dope because it reminds of Pac…but it’s not him. It was dope and sad at the same time. You know why? [Because] it was a hologram. It was good to see Pac onstage, but it wasn’t Pac.”

Although some people were pleasantly surprised by the Tupac projection, there are others who felt it tainted the artistry, or some who were just plain ol’ creeped out by it. This raises the ultimate question, Who can do what with the artists’ image in the event of their death?

Graphic companies who plan on re-enacting their own holograms should seek

permission from the estate, right of copyright, and information on right of publicity and false sponsorship and false endorsement.

“I wouldn’t mind it happening to me because that only means I left a dent in the game enough for them to want to bring me back. But if I’m still living, I’m against it. I don’t want to see a younger version of me up there,” Crooked I laughs. “It might be that way soon. What happens when the whole crowd is a hologram? What happens when nobody is going to crowds physically?”

– From Issue 253.

Words By Courtney Brown