When Kanye West left school in 1996, he dreamed of platinum plaques lining his walls, not diplomas, and his mother was initially disappointed by her son’s decisions. “As an educator, I decided there was no way a child of mine would not have at least one degree,” says Dr. West, sounding eerily like a skit on her son’s album. “But it was apparent to me he was moving ahead with his dreams.” Kanye’s American Idol aspirations seemed within reach when he flew to New York for a meeting with Columbia Records. He was close to getting signed, but his lofty boasts caught the wrong ears.

“I met with Mike Mauldin [at Columbia Records] and I said, ‘I want to be bigger than Michael Jackson. I want to be bigger than Jermaine Dupri,’” he recalls. “I was just saying that to pump myself up to them but I didn’t know Dupri’s real last name was Mauldin and that he was [Mike Mauldin’s] son. Then I was hit with those three words: ‘We’ll call you.’”

Forget a deal; Kanye couldn’t even catch a cab after that meeting and he headed by to his mom’s pad in Chicago. “One summer he was totally destitute and didn’t have money for a haircut or gas for his car,” says Dr. West. “But never once did Kanye get distraught enough to quit.” With some willing mentors, Kanye improved his production skills. He picked up acute sampling tips from No. I.D. and refined his drums with the help of Dug Infinite. Working under Deric “D-Dot” Angelittie, Kanye logged some early production credits and then hooked up with former Roc-A-Fella A&R Hip-Hop, who introduced him to Jay-Z. But ironically, his achievements behind the boards would only hinder his dogged pursuit for solo stardom.

“No label would sign me,” says Kanye, who played future hits “Jesus Walks” and “Two Words” for potential suitors. “There would always be someone saying, ‘He’s just a producer.’ I just hope those people read these words. Read them and weep.”

Kanye eventually signed to Roc-A-Fella Records in July 2002 and continued to work on his debut album, until a near fatal even changed his life. In October 2002, he was involved in a serious car accident in L.A. Having suffered multiple facial injuries including a broken jaw, Kanye’s career was in jeopardy.

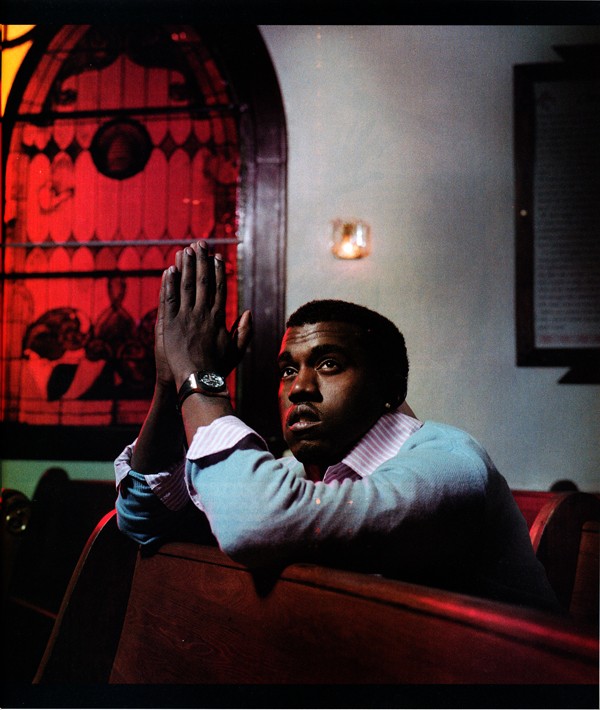

“Me breaking my mouth right before it was my time to shine was like a parent hitting a short so he knows how to act,” he says of the disaster that wrought “Through the Wire.” “Basically, God was saying, ‘Kanye, I’m about to give you the world. Don’t misuse it.’”

The inspirational “Through the Wire,” recorded while his mouth was wired shut, personifies Kanye’s greatest quality as an MC: his ability to inject humor into the most harrowing personal experiences described in his lyrics. “All my songs are about something that was negative and how God can help you through it,” he says. “Like how a minister will bring up problems in service; I try to do that lyrically. I have a responsibility to other Black men around me to help us make sane decisions and use our heads instead of always trying to look cool.”

Realizing he may be getting a tad preachy, he quickly adds, “The thing is, I’m not no lame. I still like girls and everything.” Ironically, his biggest hit to date, Twista’s “Slow Jamz” is a lighthearted party romp dedicated to the ladies. With its jabs at Michael Jackson, it became the number one record in the country this February, but Kanye remembers when not everyone was keen on his quiet storm.

“Fucking critics tried to judge it and thought the song was a joke,” he says. “It was Jay-Z’s idea to take “Slow Jamz” off my album and give it to Twista. That way I got promotion and Twista got a smash single. Jay-Z’s a genius. What more can I say?”

Say You Gonna Be…

Following a whirlwind day of publicity, Kanye West is attempting to relax at Chicago’s pos W Hotel. Lying horizontally across the plush queen-size bed, he’s on his cellphone discussing the final writing splits for The College Dropout, while devouring some peanut M&Ms. Members of his entourage joke about the hectic itineraries, but his work ethic is what elevated “Through the Wire” from a feel-good local hit to a national anthem.

And once “Slow Jamz” hit, Kanye West immediately became not only a top priority at Def Jam, but also the first superstar in the post-Jay-Z era of Roc-A-Fella Reocrds. Surprisingly, taking umbrage at such statements was label-mate Memphis Bleek. “Kanye didn’t put in no work,” Bleek said in a December 2003 interview published online. “I didn’t know a new artist can be mentioned in the same sentence as me and Beans so quickly.”

Not only is Kanye eager to quell talk of any problems, he agrees with Bleek’s comments. ‘He’s right,” Kanye says. “I wasn’t there and I didn’t pay all the dues they been through to build up Roc-A-Fella. I’m just kind of riding the wave. Bleek showed me some of the most love. So regardless of whatever they wanted to print on the Internet, I know what relationship me and Bleek have personally.”