Mass incarceration of African-American men at alarming rates has been an issue plaguing the Black community and the United States for years. Ending the practice of handing out harsh sentences to non-violent offenders in general is already a constant topic of discussion, but two dedicated filmmakers are looking to take things a step further. The effects of taking these men away from their families for extended periods of time, as well as the lack of resources available for previously incarcerated citizens looking to make a decent living once released are two intricate aspects of the story that we don’t hear much about. The Return documentary, premiered at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, tells the stories of two African-American men incarcerated for non-violent offenses as they prepare to be released from prison early. The cameras follow the men and their families as they react to the news that their loved ones would be coming home in light of the passing of the Proposition 36 Act and chronicles their journeys once they are released. Prop 36 drastically modified California’s harsh Three Strikes Rule to allow future-convicted and currently-imprisoned non-violent offenders to receive reduced sentences in exchange for probation.

Shortly after checking out the film, we spoke with directors Kelly Duane de la Vega and Katie Galloway, along with one of the film’s characters Bilal Chatman, to get more insight on the overall process of creating the documentary, the effects that the film had on the families, what actions they’d hope to see from our politicians on this issue and much more. Check out our interview below.

How long has The Return documentary been in the making?

Kelly: For us, this particular project was a long time coming in that both Katie and I have been very dedicated to the subject of shedding light on this problem in the criminal justice system. We started this a little bit before Prop 36 passed and in the summer of 2012, we did a series of short format pieces on non-violent offenders serving life sentences in California, two of which were women and one of which the film is dedicated to. When it passed, it passed overwhelmingly. 70 percent of California voted to pass this and it passed in the most liberal and the most conservative counties in the state. When it passed, we were very very excited to have the opportunity to film such a historic implementation for the first time in our nation’s history that voters voted to scale down the sentences of the currently incarcerated. We spent a great deal of time building relationships with various families, including the Anderson family and Bilal’s family, who ultimately became our central characters.

Was it difficult to convince the families and the main characters the story was going to be told in a way that would accurately depict their experiences?

Kelly: We actually sat and met with Kenneth [Anderson]’s family without the cameras and spent time with them where we told them they could ask us whatever they wanted. We talked about our previous work and we asked them to really think about how much they’d be willing to allow us into their lives. We realized that with some of our characters from earlier on, they were initially excited about the idea of it, but then when they got out and things got hard, they really didn’t want that on film. So with the Anderson family, we were very upfront about how much we imagined being in their lives and we asked them to think long and hard about it. And they really did. It took them over month to get back to us but, when they did they said they were all in. And they were all in for their own reasons. [Kenneth’s wife] Monica said it well, she said that what she had to go through was incredibly difficult and incredibly painful and she wanted to do something to help other people in her situation by bringing awareness about the effects it has on the wives and families.

Later, Katie and I flew down to L.A and showed the film to just the Anderson family to get their thoughts and feedback. It’s very much our intent to raise the voices of those whose voices aren’t typically in mainstream media and make sure that we do it in an authentic way where they feel like their stories were fairly and authentically represented. So, we showed it to them and they felt very good about the film.

The film did a great job of balancing between educating about Prop 36 and showing the stories of these families. Was that intentional?

Katie: Well, we do character driven stories as a way of looking at national issues. And not just about what was happening in California. You know, the Three Strikes Law was one of the most notorious examples of excessive sentencing in the U.S. Our sentences are 5 to 12 times the length of other industrialized countries for comparable crimes. Our prison population, more than half of the population is “non-violent” and then those who are “violent,” there’s a lot of complicated nuances to the law. It’s not always what people think. They’re doing extremely long sentences for the crimes they’ve committed. So, that was one of our top of the line messages that we wanted to convey about what’s been happening nationally. We wanted to convey that what’s going on in the U.S. today is unlike any other industrialized country and unlike any other time in our history. It’s so off the charts because there’s so little focus on rehabilitation in our system. After 4 decades of these policies, we wanted to sort of re-educate and re-socialize the nation as much as possible along with all the other people working on doing that. In terms of what we want the audience to take away, we wanted to turn the redemption narrative on its’ head. We have asked, for so many years, can people coming out redeem themselves? What we wanted to show were the effects after decades of over-criminalization and misrepresentation of people of color and poor people; criminalizing and punishing mental illness and criminalizing addiction instead of treating it as a health issue. It’s a sick system and it needs to be healed.

For you Bilal, what were some things that surprised you about yourself and how you navigated through being released after seeing it all on film?

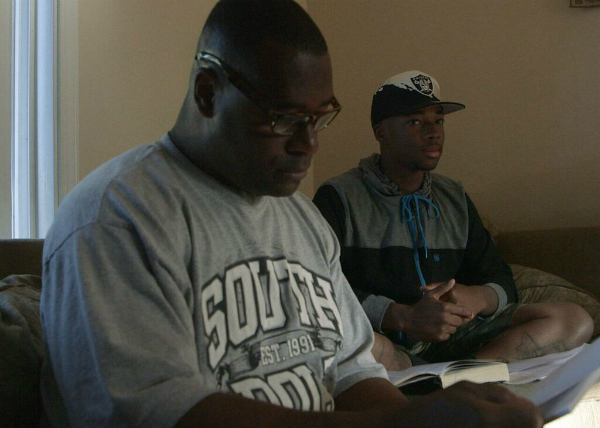

Bilal: When I looked at myself, at the beginning of my journey, I was looking at my mindset. What they didn’t capture in its’ entirety was that [that table shown in the film] was where I sat everyday. I sat there and I went through programs and books and everything that was essential to my success. Where do you go if you need housing or shoes? How do you build a resume? So, I kind of put together a book of it all and when someone in a similar situation would ask me questions, I would show them. I was also pleasantly surprised to see that one clip where I was shown with a house full of guys kind of walking around and doing their own thing, but I was still able to stay really, really focused.

You all spoke briefly about the positive feedback you’ve gotten from visiting prisons and speaking to the population there. Can you talk a little more about that and any plans to continue that?

Bilal: Listen, I’m gonna challenge this whole team to try to make that happen in jails and prisons around the country. When I was inside, we never really had a chance because we didn’t see anybody that looks like us, sounds like us, talks us who had been successful in doing this. Everybody comes in and tells us exactly what we need to do with our lives when we’re released, but they’d never been in our shoes in the beginning. So, for those guys to see somebody like me that’s been in their shoes and was able to come out and find success, it gives them hope, factual hope. People tell us it can happen but we don’t see anybody do it. Most guys who are returning citizens become repeat offenders. They’ve tried one, two, three times and they can’t get it right. Also, with regard to the lack of resources; a tooth brush, a bus pass, little things like that make a world of difference for guys coming out who have nothing. We need somebody that’s gonna assist us with getting a job and help us with some of the expenses associated with that in the beginning. Some people would want to go down and get some clothes for an interview but don’t have any money for a pair of shoes and a white shirt that fits after being gone for so long. Even if it’s some used clothes that fit you, you know? Those things were important that we had this time that I never had before. And I think that when the guys saw me and talked to me and guys like me that are in there who will come out and are working on their PhD or who have already received their master’s degree, it’s exciting to show what we can give to society. Give them this opportunity and you will see.

For the directors, what made you decide against featuring women as the main characters or subjects in the documentary?

Kelly: From our perspective, in the beginning, we did two short profiles on returning citizens that were women who had been incarcerated. That said, we see Monica and [Kenneth’s daughter] Kaylisa as important, central characters in the film. And the truth is, while women are the fastest growing prison population, the vast majority of the people on the inside who are serving time are men. Meanwhile, there’s a huge number of women and children that are “serving the time” on the outside and that’s what we wanted to show. We wanted strong, powerful women in the film. We were very conscious to have Monica, Susan and Kaylisa be main characters. We wanted to show what it was like for so many women in our country who have had their husbands and fathers taken from their home and given these incredibly harsh sentences that ultimately broke up their families.

What would you hope to see done on the political front, if any of our government officials had a chance to see the film?

Katie: Our main focus right now is just keeping it in the public’s ear. We feel like it’s a significant human rights crisis in the U.S.. We do not see it as just the story of mass incarceration; it’s something that is symptomatic of so many of the misplaced priorities in the U.S.. We are talking about class and race disparity, drug addiction and mental health. It’s a lens through which we make a larger social critique and the answer is not just shortened sentences, although that’s a big part of it. It’s imperative that we stay true to our professed ideal of “liberty and justice for all.” We do that not just through changing things going forward, but we have about 600,00 people come out every year and what are we doing to reckon with the system that we’ve created and how it’s hurt people? Specifically, we would like to see more paths to gainful employment for people coming out and we would like to see more mental health services for people coming out. We would like there to be an increased recognition of the psychological damage that prison does and the kind of support provisions that people need coming out.

We saw one character (Kenneth) go straight home to his family after being released, while Bilal went to a transition home. Do you think not going to a transition home has a negative effect on the outcome of these stories?

Bilal: For me and my story, I can’t speak on Kenneth or his motivating factors but, I do want to make something clear. I had a loving family too, who wanted me to come home and were really surprised when I told them that I was not gonna be there. I felt that I needed to remove myself from certain people, places, things and certain triggers as I learned more about my addiction. I wanted to remove myself from the place that every time I go back, I eventually end up back in jail. So it made no sense to me to go back to the people, friends and even family members who enabled me to not have a job, or not to have to work.. I didn’t want to be there, I wanted to start slow and learn more about what it would take for me to be independent. So the transitional home, I’d never been there before. When I was arrested for drugs, I asked the D.A. and the judge if I could have a 2-year or 4-year (rehab) program. I would’ve went to a 6-year program, I don’t care. But the first thing they told me was ‘no programs period, jail only.’ So, when this opportunity came, I didn’t want to hit the ground running and end up back in the same situation I was in when I left. And believe me, it wasn’t easy. It wasn’t as easy as I’d have liked it to be but, I just utilized it to the best of my ability. I encourage people, especially those with families, to go to a transitional house and learn more about themselves to get themselves more independent first before they come home. If they don’t, to me, it seems that they come home to a lot of responsibility, bills that you have to pay and things that you have to take on that you’re just not ready to. But if you came to the transitional home and visit your family while you’re there and while you’re learning more about yourself, I think you would do better.

Are there plans to turn this into a series or show more people’s stories?

Kelly: Well, our national broadcast will take place on May 23 on POV, so we’re really excited about that. It’s a national PBS series and we’re launching our segment. We’re also doing a 10-city tour spreading the word about the project leading up to the broadcast. We’ll be in cities like DC, Baltimore, Detroit, Brooklyn, L.A. and others. You can get more information about it at www.thereturnproject.com.

**

Be sure to check out the premiere of PBS premiere of The Return on May 23. For a look at the trailer along with more information on the project and how you can get involved, visit the official website HERE.